English

Back to Earth: Spatial Concept

It has become a commonplace that we live in a world of plenty, in a throwaway society which, in order to satisfy its short term needs, is happy to greatly endanger the future of upcoming generations. Nonetheless there seem to be areas where careful, considerate use of resources plays at best a minor part. When it comes to art for example, thinking about sustainability takes a backseat as a matter of course. On the one hand we can witness this in international inter-art-institution loans by way of constantly growing demands on conservation involving enormous technical efforts and accordingly a consumption of energy that is permanently increasing. On the other hand we can see this in the large exhibition centres for contemporary art where ever more extravagant spatial constructions are mounted to house exhibitions that only last a few months. Acres of chipboard is used as if there’s no tomorrow, only to be thrown out after it has done its duty. The only industry which behaves in an even more careless manner is trade fair construction, where elaborate structures are completely ‘disposed of’ after only a few days. In the cultural community this argument is often refuted by pointing out that the important purpose justifies the expense (implying that this does not apply to trade fair buildings whose function is much more mundane…). This proves to be an entirely out-of-date exaltation of the artistic object, a clinging to a Beaux-Arts mentality better suited to the 19th century. Ironically, institutions such as the International Council of Museums (ICOM) practise this fetishisation of the ‘objet d’art’, seemingly oblivious to the actual developments in contemporary arts. This leads to the absurd situation where works which explicitly escape this fetishisation in terms of their content automatically fall prey to it when exhibited (a prime example of this is Duchamp’s urinal, which is part of the Back to Earth exhibition). Another argument refers to the high insurance values of the art works, which again is ironic, since the fact that the individual objects are seen as putative cultural assets highlights their financial worth as mere investments. The subordination of supposedly second-rate sustainability considerations to a ‘high culture’ is a development which needs to be questioned. The concept for the exhibition Back to Earth is a passionate plea for a more sustainable and responsible approach to the presentation and transportation of art. At the same time it is a plea for a more instinctive approach to art as an integral part of the reality of everyday life in an open and pluralistic society.

Glass house instead of ‘white cube’

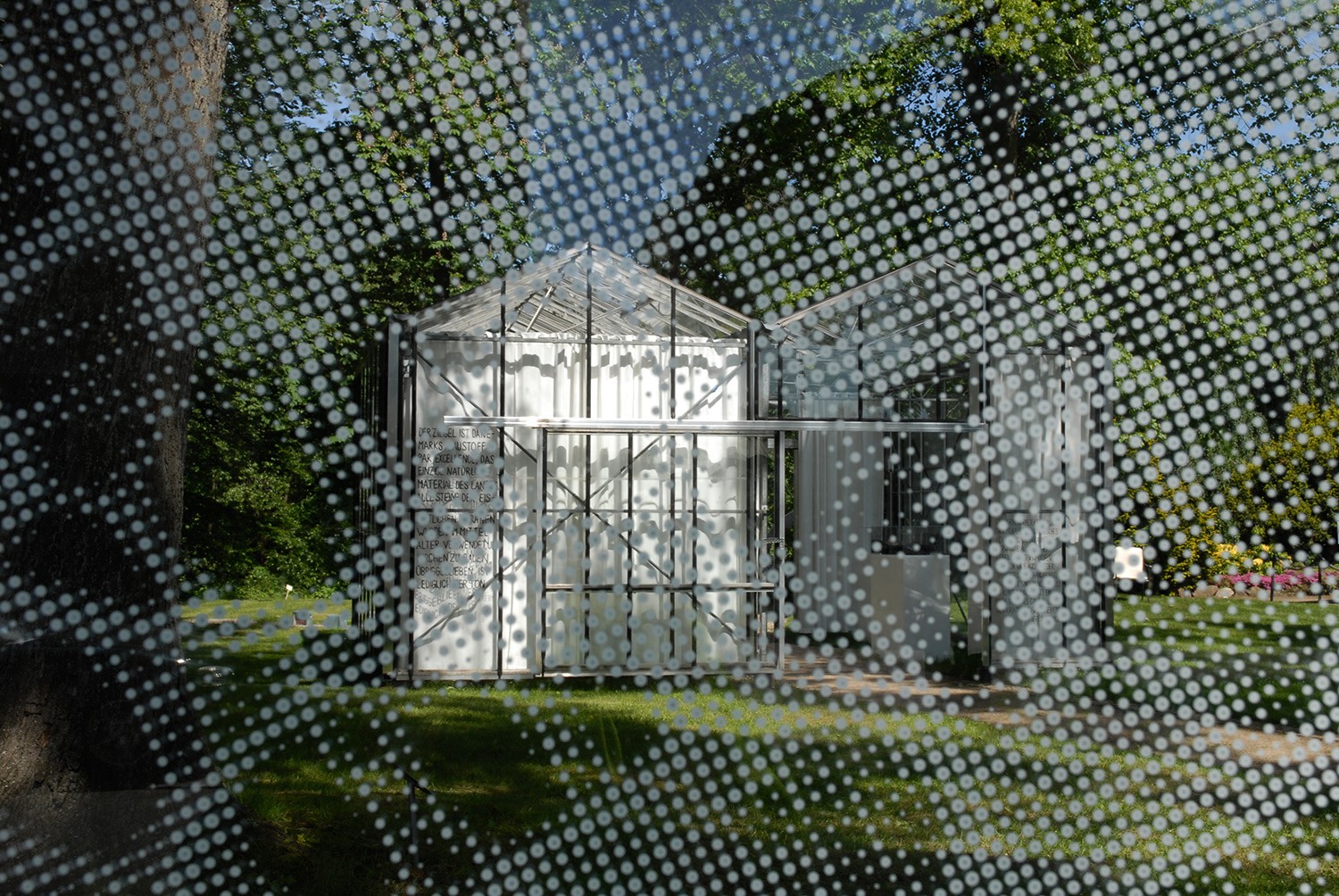

What initially strikes the visitor are the greenhouses strewn all over the park. They are second-hand, which means that before they came to the Gerisch Foundation, they were used for growing plants. At the end of this exhibition they will be sold on and reused in a different location as greenhouses again. Their modular construction from individual elements means they can be re-assembled many times and allows them to be reused in both small and large facilities. The greenhouses do not look new and a conscious decision was made to leave details which were in part inelegant or merely functional.

In this sequence of use, the objects shown in this exhibition have the same status as the cucumbers, tomatoes or tulips normally grown under their glass roofs. Under no circumstances do we undervalue the exhibits, but rather want to emphasise in a subtle, yet convincing way the elemental position of cultural products.

Our work on this concept was heavily influenced by the groundbreaking exhibition architecture by the firm of architects Lacaton & Vassal seen at documenta 12. By completely reversing standards up until then expected from museal structures, their intention was to exhibit the majority of the works in a light, open greenhouse landscape open to the park, extending seamlessly into the bucolic landscape of Karlsaue Park. This was not to be an exaltation of the object in a purpose-built, artificial space. Instead the natural space flowed through the exhibition areas joining the two to create a new, high quality cultural space never before seen.

Particularly in the context of its eventual realisation, this work has to be seen as a trailblazer for how art is presented and for the architectural manifestation of basic institutional criticism.

Finally, in 2007, the exponents of ICOM-style musealisation won a victory when the light, airy construction was covered in order to protect the exhibits from too much harmful sunlight. Enormous air-conditioning machines with gigantic hoses created an aura of a particularly dystopic Ridley Scott film in Karlsaue Park. In short, Lacaton & Vassal’s concept was turned into the opposite of what its creators had intended, and they distanced themselves in disgust from the project.

It is all the more gratifying, therefore, that we have succeeded in returning to the idea from 2007 for Back to Earth. We understand this as a bow to documenta 12 and see it as a step towards an exhibition culture which permanently confines to the past bourgeois ideas of how art should be shown.

Heterarchy

In our view, exhibits and pavilions are parts of a heterarchical strategy. The pavilions are on a par with the other buildings in the park, thus ensuring, through their visual weight too, that the different structures are of equal importance. This is particularly interesting when it comes to the Villa Wachholtz and the Gerisch residence. The representative character of these two buildings is broken up in favour of a more equal ensemble. The emphasis on a superordinate and coherent unit is also key to where the individual exhibits are positioned inside the greenhouses. Because the walls are transparent the view can flit from one to another thus putting them in relation not only to one another, but also to the permanent exhibits in the sculpture park. This creates a connectivity which conveys to the recipient the specific unity of the exhibition. Both temporary and permanent exhibits form an interconnected entity for a certain period of time.

The individual works are arranged along the existing path in the park. This is less a didactic strategy than another element in the evocation of the intended naturalness on which the sculpture park is already based. This means that the visitor only really strolls through a park where he/she can casually take in a number of different works of art along the paths and now also in the glass houses right next to them.

More than other topics, ‘ceramics’ includes a huge number of different works, ranging from everyday utility items which can be replicated indefinitely as industrial products to individual pieces with a specifically artistic intention. The emphasis on equality and the connection between all individual objects are deliberate. It is an invitation to the visitor to reassess and – maybe hone – their own perception.

Roger Bundschuh

Deutsch

Dass wir in einer Welt des Überflusses, in einer Wegwerfgesellschaft leben, die zur Befriedigung kurzfristiger Bedürfnisse bereit ist, die Zukunft kommender Generationen nachhaltig zu gefährden, ist zu einem Gemeinplatz geworden. Dennoch scheint es Bereiche zu geben, in denen der sorgfältige und schonende Umgang mit den Ressourcen eine bestenfalls untergeordnete Rolle spielt: Sobald es um Kunst geht, treten Nachhaltigkeitsüberlegungen wie selbstverständlich in den Hintergrund. Wir können dies zum einen im internationalen Leihverkehr an stetig wachsenden konservatorischen Anforderungen sehen, die einen enormen technischen Aufwand und einen dementsprechenden dauerhaft ansteigenden Energieverbrauch nach sich ziehen, zum anderen an der gängigen Praxis fast aller großen Ausstellungshäuser für zeitgenössische Kunst beobachten, immer aufwendigere räumliche Inszenierungen für nur wenige Monate dauernde Ausstellungen zu betreiben. Quadratkilometer von Spanplatten werden sorglos verbaut, nur um sie, nachdem sie ihre Schuldigkeit getan haben, auf den Müll zu werfen. Die einzige Branche, die hier noch problematischer agiert, ist der Messebau; hier werden die aufwendigen Inszenierungen schon nach wenigen Tagen komplett „entsorgt”.

- Team

- Fabian Schwade, Yannis Efstathiou

- Type

- Exhibitiondesign

- Photographer

- Marianne Obst/Gerisch Stiftung